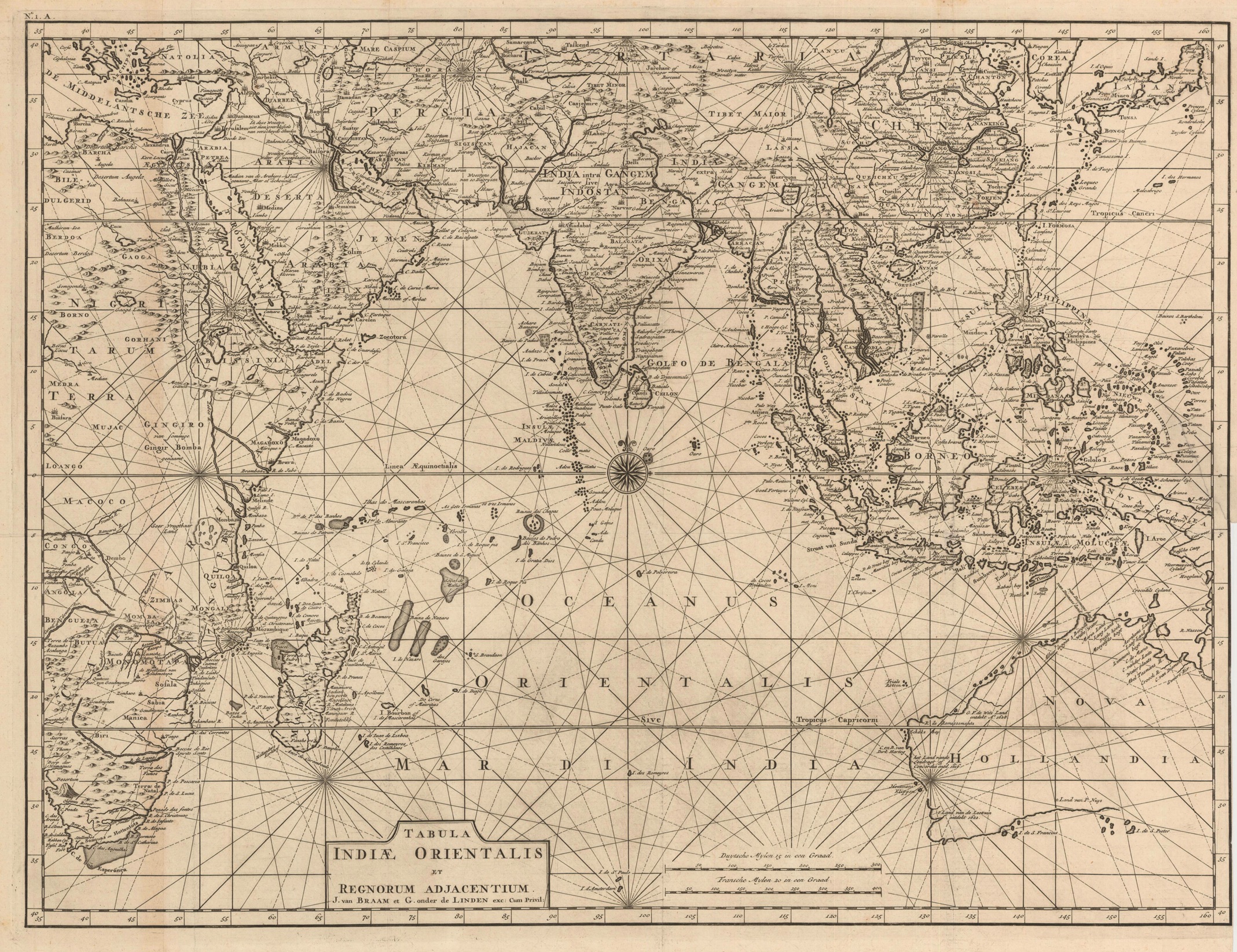

Antique Map South-East Asia by Valentijn

Antique Map South-East Asia by Valentijn titled ‘Tabula Indiae Orientalis et Regnorum Adjacentium J. Van Braam et G. onder de Linden (..)’.

Early 18th century map of Australia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, from Valentyn’s Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, one of the earliest contemporary maps to report information drawn from the Dutch V.O.C. during the period.

This excellent map details the Middle East, the Indian Ocean, the Far East, and much of Australia, based on careful compilation of the best available sources by the brilliant and entertaining Dutch chronicler, François Valentijn.

The map features a fine depiction of the outlines of the western two-thirds of Australia, based on the discoveries of explorers working for the Dutch East India Company (the VOC). These include Willem Jansz’s discoveries in the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1606; the encounters of Dirk Hartog in 1616, the crew of the Leeuwin in 1622, Gerrit Frederiksz de Witt in 1627, and Pieter Nuyts in 1627, in Western Australia; and Jan Cartensz and Willem van Colster’s discoveries in Northern Australia in 1623.

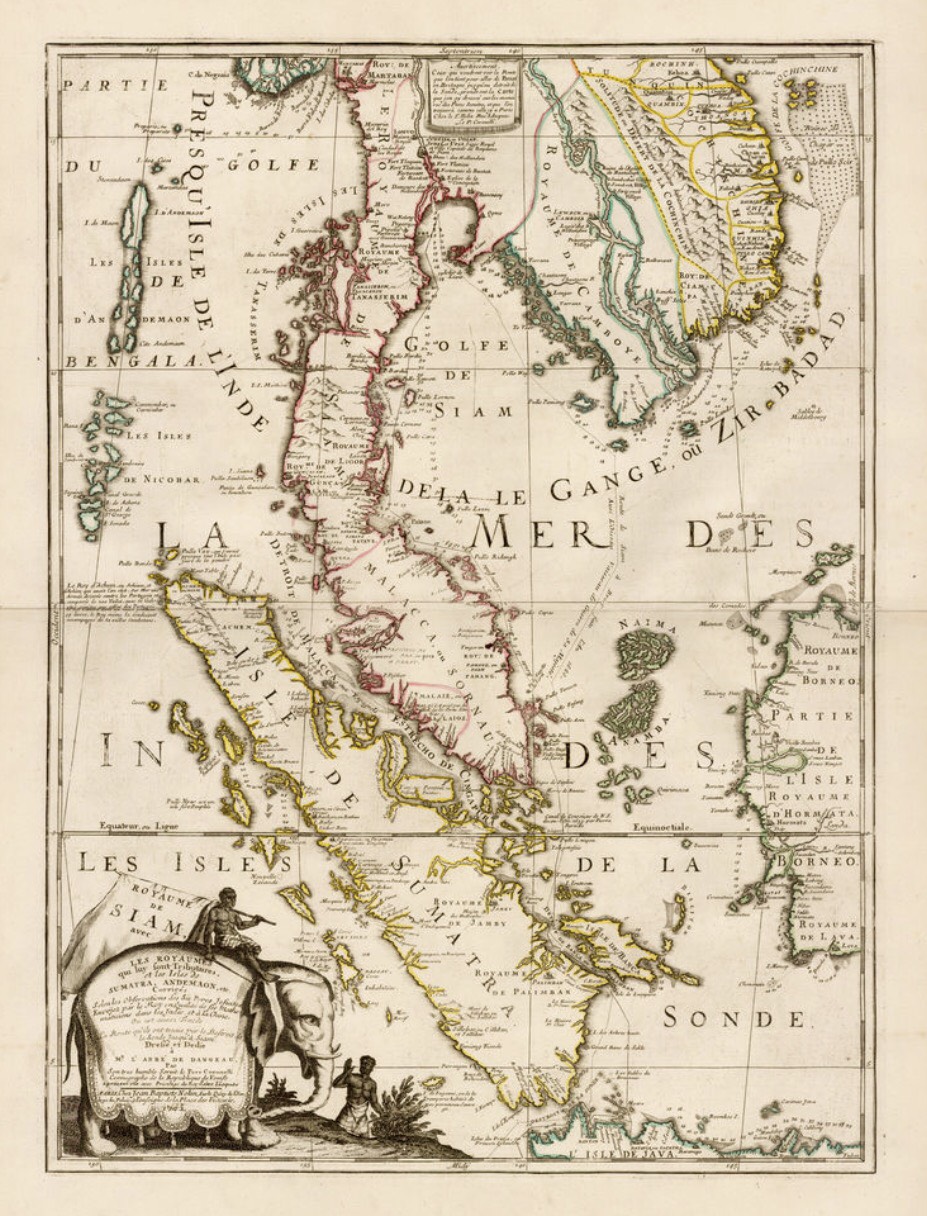

The Indonesian Archipelago is well-formed based on VOC knowledge, except that the shape of New Guinea still remains ambiguous. The Philippines are shown in the configuration utilized prior to the publication of Padre Pedro Murillo Velarde’s map in 1744. Continental Southeast Asia assumes a refined form, and includes the intelligence gathered by the French embassy to Siam, made shortly before Western contact with the kingdom was cut-off in 1688.

Further north in Asia, the coasts of China are relatively well formed, based on Jesuit surveys, most notably those conducted by Martino Martini in the 1640s and 1650s. Korea is correctly shown as a peninsula, albeit of a somewhat nebulous form. Notably, Valentijn does not incorporate and was likely unaware of the groundbreaking surveys of China and Korea contained in the Chinese Kangxi Atlas (1718-9), which was yet to reach Europe. The southern main islands of Japan are relatively well formed, based on the charting of VOC mariners operating out of Nagasaki.

The coasts of India, Arabia and Africa are conveyed in a progressive manner, based on extensive navigational experience and innumerable surveys conducted by the Portuguese and the Dutch. Notably, ‘I. St. Maria’ (St. Mary’s Island) on Madagascar was then the pirate capital of the World and a place to be avoided by ‘legitimate’ mariners.

Notably, the map features highly advanced detail with respect to the interior of southern India, based on the work of the French Jesuit Jean-Venant Bouchet (1655-1732), who was the first European to extensively map the Deccan. In 1719, he sent a manuscript map to Paris, which was first published in 1722. Valentijn’s inclusion of this information is therefore quite early.

François Valentijn: A Brilliant Braggart

Francois Valentijn (1666–1727) was a minister, naturalist and writer. He is best known for his Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien(“Old and New East-India”), a book about the history of the Dutch East India Company and the countries of the Far East.

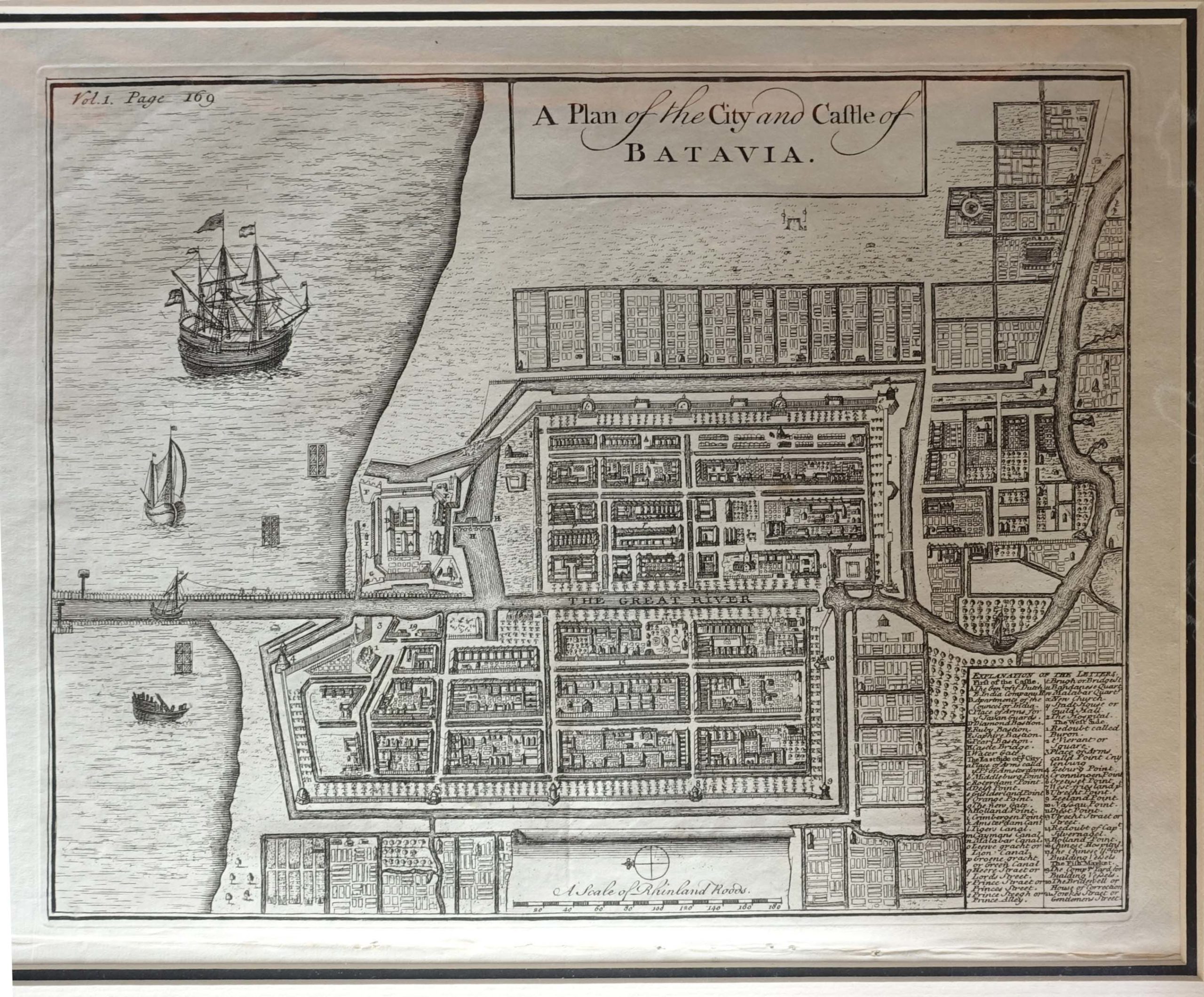

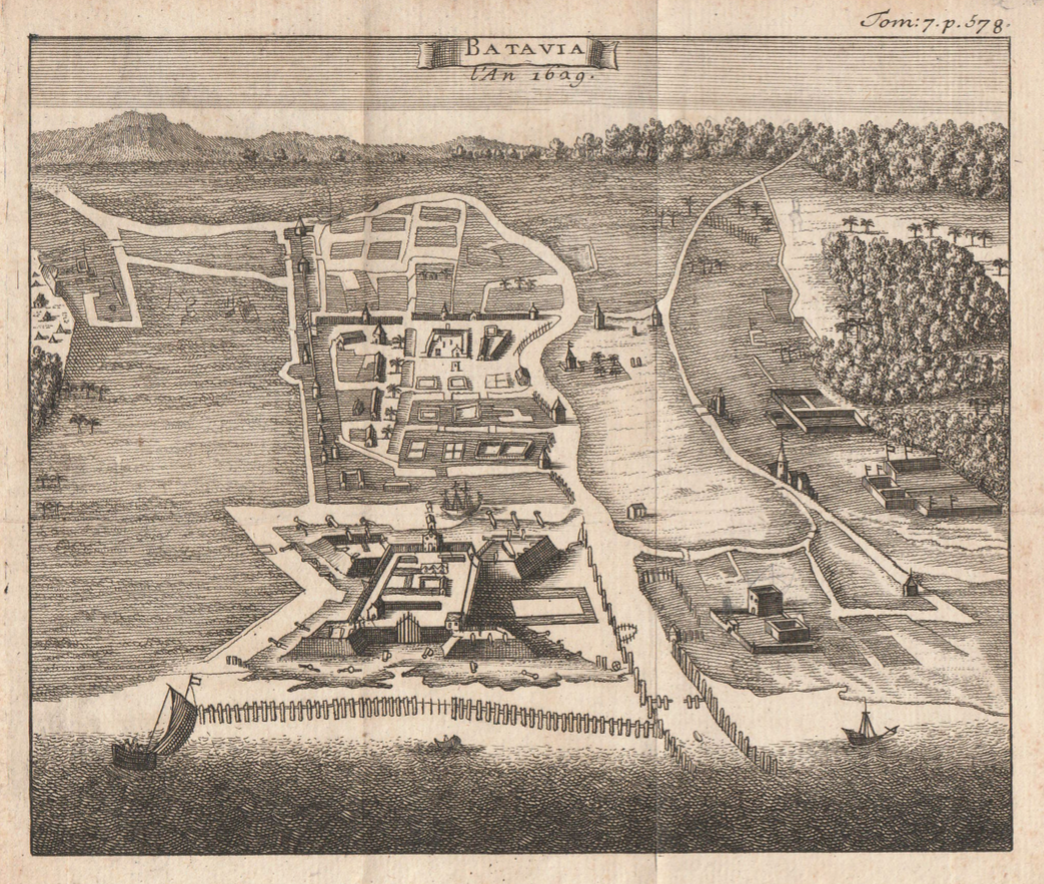

Valentijn was born in 1666 in Dordrecht, Holland, but spent significant time in the tropics, notably in Ambon, in the Maluku Archipelago,. In total, Valentijn lived in the East Indies 16 years. Valentijn was first employed by the Dutch V.O.C. or East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) at the age of 19, where he served as Minister to the East Indies. He returned to Holland for about ten years, before returning to the Indies in 1705 where he was to serve as Army Chaplain on an expedition in eastern Java. He again returned to Dordrecht where he wrote his Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (1724–26), a massive work of five parts published in eight volumes and containing over one thousand illustrations and including some of the most accurate maps of the Indies of the time. He died in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1727.

Valentijn probably had access to the V.O.C.’s archive of maps and geographic secrets which they had always guarded jealously. Johannes Van Keulen II became Hydrographer to the V.O.C. in the same year Valentijn’s book was published. It was in Van Keulens time that many of the VOC charts were published, one signal of the decline of Dutch dominance in Spice Trade. Valentijn was fortunate to have seen his work published, as the VOC (Dutch East India Company) strictly enforced a policy prohibiting former employees from publishing anything about the region or their colonial administration. And while, as Suárez notes, by the mid-18th Century the Dutch no longer feared sharing geographic secrets, the execution of this policy was still erratic and based on personal motives.

While Valentijn’s maps and diagrams were prized possessions, his scholarship, judging by contemporary standards, was not of the highest integrity. While current standards of referencing and plagiarism were not in effect during the 18th Century, Valentijn’s borrowed liberally from other scientists’ and writers. E.M Beekman referred to Valentijn as an “exasperating Dutch braggart,” but nevertheless cites him as an important figure and given his writing style, diction and penchant for story, one of the greatest Dutch prose writers of the time—going so far as to suggest comparison between one of the various stories in his work and a Chaucerian tale.

Valentijn’s work is one of the truly great maps showcasing the European geographical knowledge of South and East Asia and Australia from the early 18th Century. ( References: Tooley, R.V. (Australia) )