Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s ‘Itinerario’ (1598)

Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s ‘Itinerario’ ~ ‘The Key to the East’.

(Translated: ‘itinerary’ a planned route or journey)

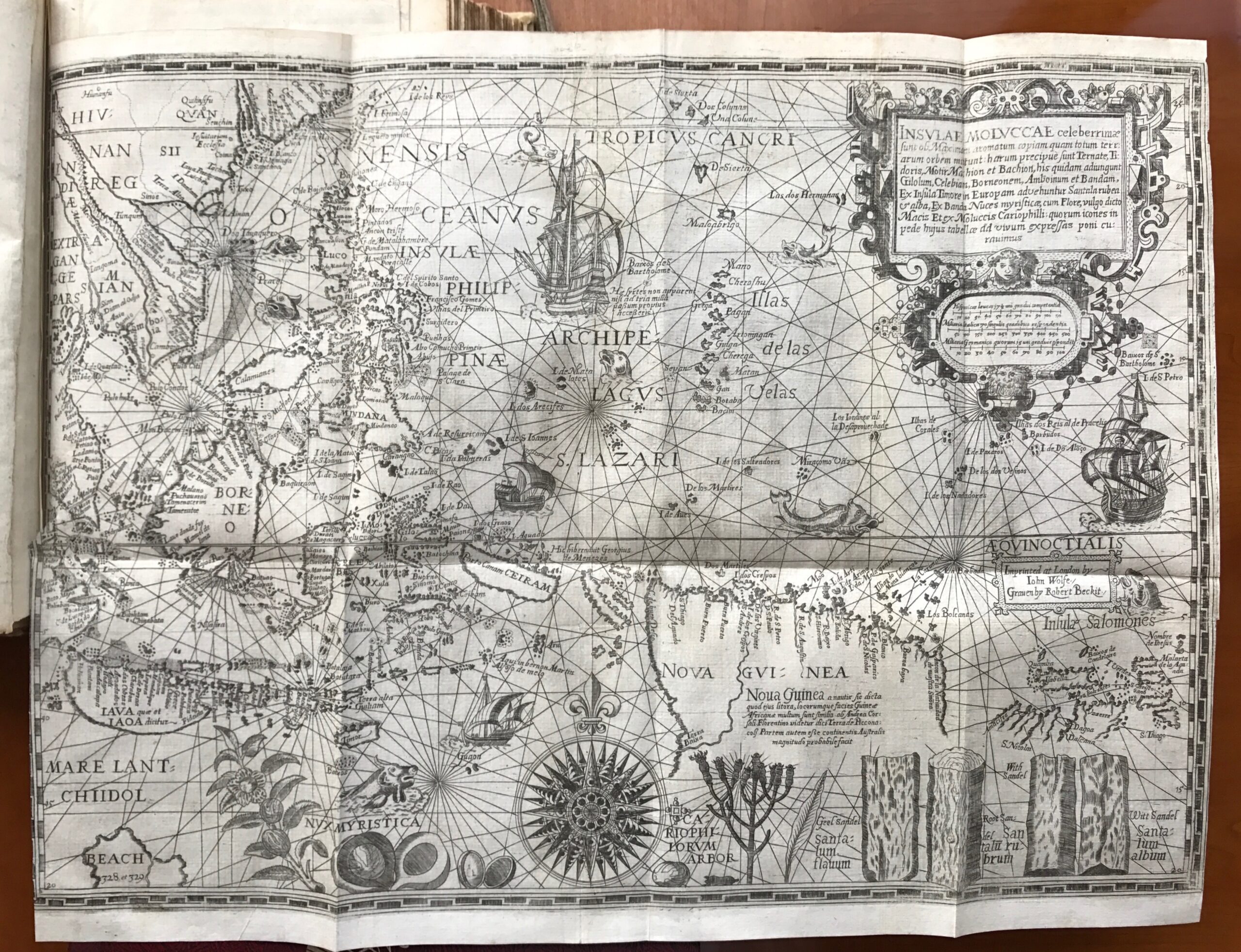

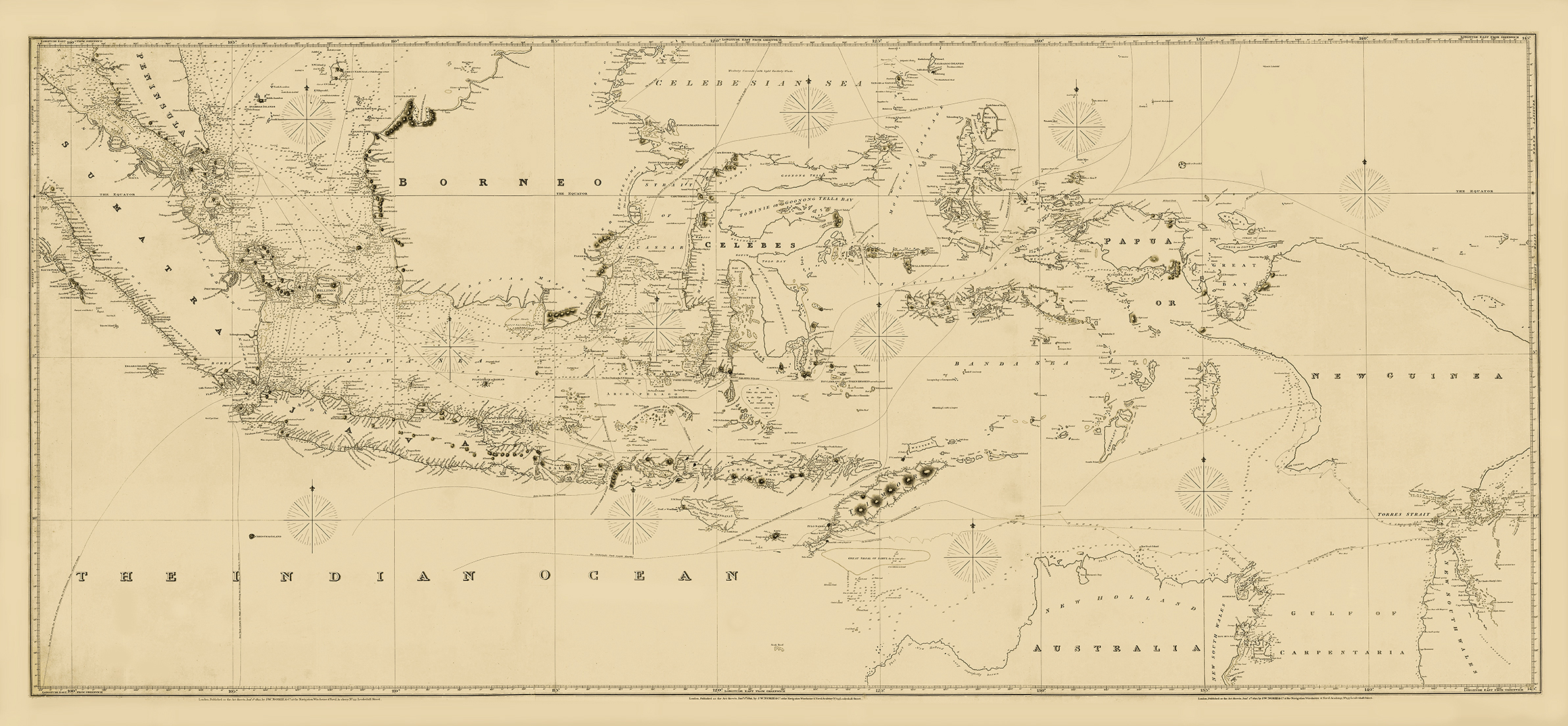

Title: his Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies. Devided into Foure Bookes Printed at London by JOHN WOLFE Printer to ye Honourable Cittie of LONDON. Published in London in 1598.

Contains illustrated copper title and 3 engr. title vignettes (small maps) as well as 10 folding copper maps and 3 folding copper plates with views of S. Helena & Ascension (lower margin usually cut away, here untrimmed) and 4 woodcut maps in text. Additionally with 25 plates (depicting costumes and plants) and 2 maps of Goa and Angra from the orig.

The Key to the East,

For most of the 17th century the Dutch East India Company, or VOC, brought wealth and prestige to the Low Countries, ushering in what would be known as the Dutch Golden Age. Business was booming, profits were soaring, and the greatly expanded middle class flaunted its newly acquired wealth. It was an age of masterpiece paintings and scientific breakthroughs.

What allowed the VOC, established in 1602, to amass such vast fortunes at breakneck speed? The answer lies within this historically important and extremely rare book, that has been dubbed ‘The Key to the East’.

The young Jan Huygen van Linschoten,

Born to a well-off family in Haarlem in 1562, Jan Huygen van Linschoten grew up in the town of Enkhuizen, at the time already home to a thriving fishing industry. His father was an innkeeper, which no doubt allowed the young Van Linschoten to encounter many travellers and sailors eager to share stories of their adventures. His head must have been filled with visions of the strange and exotic at a young age. In the opening paragraphs of the Itinerario he states that, as a child, he ‘took no small delight’ in the ‘reading of histories and strange adventures’.

He likely attended the Latin school in Enkhuizen, where he learned to read and write, do mathematics, and perhaps also read Latin. At the age of sixteen, Van Linschoten followed in the footsteps of his older stepbrothers by traveling to Seville, Spain, to find employment and learn a trade, as was customary for young men in his social sphere. He eventually found his way to Lisbon in the wake of the Spanish King Philip II, who took over control of the Portuguese Crown. Once there he was taken into the company of João Vicente da Fonseca, archbishop of Goa, a city and region in India. He promptly left European shores with his new employer, in search of the adventures he had so often envisioned.

Van Linschoten took a special interest in learning about Goa itself, studying its inhabitants, their habits, their culture and religion, and the local plant and animal life. Although he would not have had much direct contact with the natives, his protracted stay allowed him to learn much by simple observation. Additionally, he must have picked up a great deal of nautical and mercantile information by visiting the docks, both of which provided him with unique insight into the structure of the Portuguese empire in the East. All of this information, the stories, the gossip, and the news he acquired in Goa over time laid the groundwork for the preparation of his greatest achievement.

Return Home,

Van Linschoten greatly enjoyed his life in Goa. His letters back home betray as much: at one point he even says he could see himself remaining there for the rest of his life. He declined the opportunity to join an expedition headed for China. While his thirst for adventure may have been real, he was not reckless: he considered the proposition too risky, and was not prepared to lose money. All the signs pointed to him staying in Goa for many more years to come.

Then, sadly, disaster struck, and before long he embarked on his journey back home at the end of 1588. The cause was the death of both his stepbrother and of his mentor, the archbishop, who had already returned to Portugal at this point. He never laid eyes on Goa again. His homecoming was delayed by a shipwreck near the Azores. Van Linschoten decided to remain on the island of Terceira to oversee the salvage of lost goods. This also afforded him the opportunity to write a description of the island. He eventually found his way back to Enkhuizen in September 1592, where he found work as treasurer and became engaged to Reynu Meynertsdr Seymens, who was already three months pregnant at the time of their marriage.

Van Linschoten did not become complacent after coming home. He took part in Willem Barentsz’s 1594 attempt to find an alternative route to Asia through a northern passage. Like Barentsz, Van Linschoten believed that to be the most viable option for traveling to Asia, as it meant completely avoiding any Portuguese opposition along the way. Complete knowledge of the northern regions was still sparse, and many believed the road north to be much shorter than the southern route. Van Linschoten participated in two attempts as advisor and overseer, but did not join the third and fateful expedition of 1596, which would prove fatal to Barentsz himself.

Linschoten’s ‘Itinerario’,

Linschoten’s Itinerario actually consists of three several books in one. Each with its own title, title page, and page count. The first part is a report of the journey Van Linschoten undertook from Lisbon to Goa and back again. It contains material on several countries in the area, but mostly extensive information on Goa itself, its surroundings, the state of affairs in Portuguese India, and valuable information on regions that were still as good as unknown to most Europeans.

Aside from being very appealing to the interested lay person, this text also taught merchants which spices could be obtained where, and at what cost. More than that, it revealed weaknesses in the Portuguese grip on the region, especially detailing that their hold on the Indonesian territories was strenuous at best. It was there that the Dutch were able to establish their strongest base in the region and drive out the Portuguese almost entirely.

The book proved to be valuable to the more professional reader, rather than to a general audience. It was this Reys-geschrift, or ‘Travel Writing’, that contained the information that turned out to be so valuable to the establishment of the VOC, and thereby Dutch dominance in East Asian trade and colonization. These instructions not only detailed the best passages for traveling from Portugal to its Indonesian colonies, but also between India, the entire Indian archipelago, China, and Japan. In short, it provided the information the Portuguese had for so long successfully shielded from prying eyes.

The End of Van Linschoten’s Travels,

How did Linschoten fare under the success of his book? Although its use and popularity would start to decline during the 17th century, this was not yet the case during his lifetime. There is no denying he became a man of recognition and influence, as evidenced by his marrying into a family of regents, and his mixing with the local elite. He spent the remaining years of his life working as the treasurer of Enkhuizen, as a man of quite some financial means and influence. Even so, he was faced with disappointment near the end of the life: he applied for a state pension, but was rejected on the basis that past royalties and earnings from his book should have been plentiful enough to support him. Whether or not that was the case we will never know, as he died not long after in 1611 at the age of 48. His legacy has lasted many a lifetime.

Year: 1598

Condition: Text leaves partly slightly browned (mostly in the margins), here and there minor staining, lower gutter with small wormtraces in the first third, maps mostly with backed resp. restored tears, 4 maps and 2 plans mounted, the map of Guinea with small cut-off at left margin (affecting printed matter).

Coloring: Black and white

Price: On request.

Inventory No. B2004-C