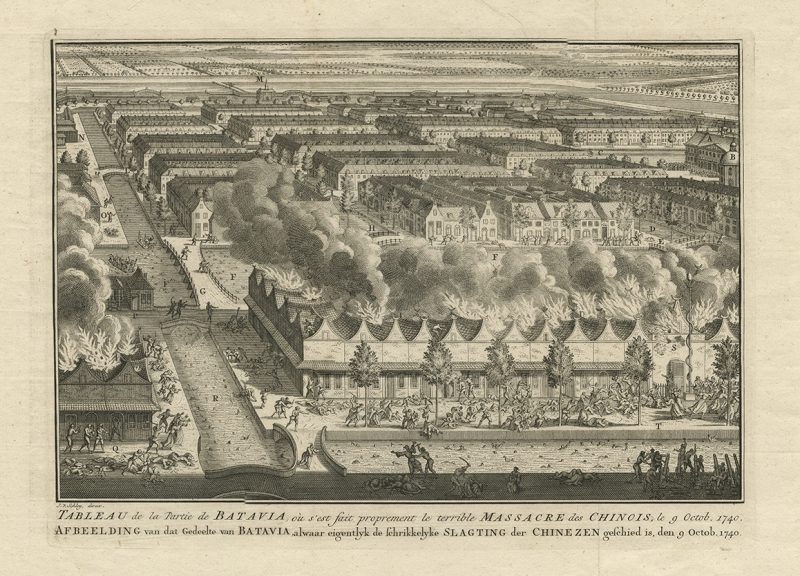

Antique Print Chinese Massacre by Van Schley (c.1740)

Antique Print Chinese Massacre by Van Schley (c.1740) titled ‘TABLEAU de la Partie de BATAVIA, ou s’est fait proprement le terrible MASSACRE des CHINOIS, le 9 Octob. 1740.

AFBEELDING van dat Gedeelte van BATAVIA, alwaar eigentlyk de fchrikkelyke SLAGTING der CHINZEN gefchied is, den 9 Octob. 1740′.

The rare mid-18th century print showing the terrible massacre of the Chinese that occurred in Batavia October 9th 1740, engraved by Adrian van der Laan of Amsterdam. The print shows Dutch troops firing cannon into Chinese houses on the banks of Kali Besar, slaughtering people as they fled their burning homes and waiting in boats to kill those that sought escape in the river; it is estimated that some 10,000 Chinese were killed. The massacre was prompted by tales of Chinese atrocities following the death of 50 Dutch soldiers at the hands of enraged Chinese sugar plantation workers who were protesting about Government repression and the declining sugar prices.

The 1740 Batavia massacre (Dutch: Chinezenmoord, literally “Murder of the Chinese”; Indonesian: Geger Pacinan, meaning “Chinatown Tumult”) was a pogrom of ethnic Chinese in the port city of Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. The violence inside the city lasted from 9 October until 22 October 1740, with minor skirmishes outside the walls continuing late into November that year. Historians have estimated that at least 10,000 ethnic Chinese were massacred; just 600 to 3,000 are believed to have survived.

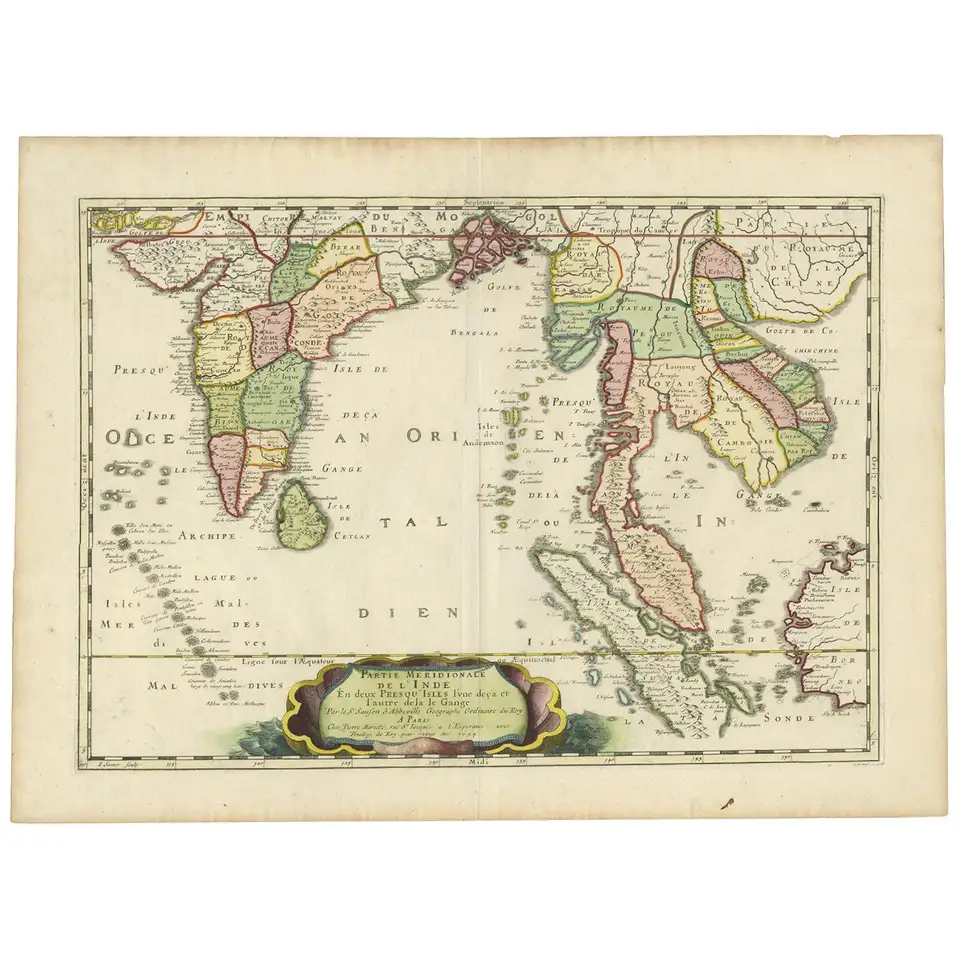

During the early years of the Dutch colonisation of the East Indies, many people of Chinese descent were contracted as skilled artisans in the construction of Batavia on the northwestern coast of Java. They also served as traders, sugar mill workers, and shopkeepers.The economic boom, precipitated by trade between the East Indies and China via the port of Batavia, increased Chinese immigration to Java. The number of ethnic Chinese in Batavia grew rapidly, reaching a total of over a 10,000 by 1740. Thousands more lived outside the city walls.

The Dutch colonials required them to carry registration papers, and deported those who did not comply back to China – the policy was tightened during the 1730s, after an outbreak of malaria killed thousands. The outbreak was followed by increased suspicion and resentment in native Indonesians and the Dutch toward the ethnic Chinese, who were growing in number and whose wealth was increasingly visible.

Wealthy Chinese were extorted by corrupt Dutch officials who threatened them with deportation, and there were rumours that deportees were not taken to their destinations but instead thrown overboard once out of sight of Java. In some accounts, they died when rioting on the ships. The deportation of ethnic Chinese caused unrest among the remaining Chinese, leading many Chinese workers to desert their jobs.

At the same time, due to economic imbalance, native occupants of Batavia became increasingly distrustful of the Chinese. Most natives were poor, and they perceived the Chinese as occupying some of the most prosperous neighbourhoods in the city. The actual situation was more complicated. Many poor Chinese living in the area around Batavia were sugar mill workers who felt equally exploited by the Dutch and Chinese elites who owned the mills. The price of sugar, however, was set by the Dutch overlords set the price for sugar, which itself caused unrest.

In the 1720s, due to an increase of exports to Europe and competitions from the West Indies, worldwide sugar prices declined and the sugar industry in the East Indies suffered considerably. By 1740, prices had dropped to half the price in 1720. As sugar was a major export, this caused considerable financial difficulties for the colony and led to further unrest.

Despite oppositions from the Dutch Council of the Indies, who did not believe the Chinese would ever attack Batavia, governor-general Valckenier called up an emergency meeting of the council in September, during which he gave orders to respond to any ethnic Chinese uprisings with deadly force. This policy continued to be opposed by his political opponent, van Imhoff.

Vermeulen (1938) suggested that the tension between the two colonial factions played a role in the ensuing massacre.

Events leading to the Massacre of October 1740

On the evening of the 1st of October, a crowd of a thousand Chinese had gathered outside the city gate, angered by Valckenier’s statements at the emergency meeting five days earlier. This was initially received incredulously by Valckenier and the council, but when a Balinese sergeant was murdered by the Chinese outside the walls, the council decided to take extraordinary measures and reinforce the guard.

On the 7th of October, hundreds of Chinese sugar mill workers revolted using custom-made weapons to loot and burn mills, and killed 50 Dutch soldiers in Meester Cornelis (now Jatinegara) and Tanah Abang. In response, the Dutch sent 1,800 regular troops, accompanied by schutterij (militia) and eleven battalions of conscripts; they established a curfew and cancelled plans for a Chinese festival. Those inside the city walls were forbidden to light candles and were forced to surrender everything “down to the smallest kitchen knife”.

The following day the Dutch repelled an attack by up to 10,000 ethnic Chinese, led by groups from nearby Tangerang and Bekasi, at the city’s outer walls; Raffles wrote that 1,789 Chinese died in this attack. In response, Valckenier called another meeting of the council on 9 October.

Meanwhile, rumours spread among the other ethnic groups in Batavia, including slaves from Bali and Sulawesi, Bugis, and Balinese troops, that the Chinese were plotting to kill, rape, or enslave them. These groups pre-emptively burned houses belonging to ethnic Chinese along Besar Stream. The Dutch followed this with an assault on Chinese settlements elsewhere in Batavia in which they burned houses and killed people.

“…pregnant and nursing women, children, and trembling old men fell on the sword. Defenseless prisoners were slaughtered like sheep…”

A few paragraphs from a diary of someone who joined the killings and the robberies:

“At first women and children were left alone and not killed. At nine o’clock the government – generally ordered all artisans to enter the city and slay all Chinese. This order was well received. And in order to be able to plunder as much as possible, everybody quickly left his job. Then the slaughtering started. The carpenters brought their axes to break open the doors and windows. People who owned firearms entered the houses and shot the Chinese inhabitants. I did too.

Because I knew that my neighbour owned a fat pig, I wanted to take it home. When the head of the carpenters saw that, he beat me and told me to kill the Chinese owner first, before taking away the pig. Because I didn’t have a pistol, I took a rice pounder as big as an arm, and beat my neighbour, who often had dinner with me, till he was dead. Although I didn’t like it, I was forced to do so, because the head carpenter stood at the door and watched me. After killing that man, I went into the room and found a pistol with many bullets. I took it and went outside and started killing at random.

After killing two-three people, I was able to butcher people without feeling the difference of killing a Chinese or a dog. In the afternoon, at one o’clock, the city was on fire, started by the Chinese themselves. They preferred to burn themselves rather than fall into our hands… Often up to five people hung themselves by the beams of their houses.

The Chinese (in Batavia) had their own hospital. We were ordered to kill all the patients except two blind man. In the city Hall there were two hundred prisoners, all were stabbed to death in order to save ammunition. On the 13th the fire stopped and there was not one Chinese left the city. All roads and alleys were full of corpses: the canals were filled with bodies, so one could cross the other side by walking over the corpses without getting ones feed wet. ”

Aftermath

Valckenier unsuccessfully requested that officers control their troops and stop the looting, the violence continued to spread until the 12th of October. Chinese patients in a hospital were taken outside and killed, and attempts to extinguish fires in areas failed.

Meanwhile, a group of 800 Dutch soldiers and 2,000 natives assaulted Kampung Gading Melati, and nearby Paninggaran. There were approximately 450 Dutch and 800 Chinese casualties in the two attacks. In retaliation, the council established a reward of two ducats for every Chinese head who surrendered. As a result, ethnic Chinese who had survived the initial assault were hunted by gangs of irregulars, who killed those Chinese they found for the reward.

On 22 October Valckenier called for all killings to cease. In a lengthy letter in which he blamed the unrest entirely on the Chinese rebels. Valckenier offered an amnesty to all Chinese, except for the leaders of the unrest, on whose heads he placed a bounty of up to 500 rijksdaalders. Outside the walls skirmishes between the Chinese rebels and the Dutch continued.

On 25 October, after almost two weeks of minor skirmishes, 500 armed Chinese approached Cadouwang (now Angke), but were repelled by the Dutch cavalry. The following day the cavalry, which consisted of 1,594 Dutch and native forces, marched on the rebel stronghold at the sugar mills, first gathered in the nearby woods and then set the mills on fire while the rebels were still inside.

Most accounts of the massacre estimate that 10,000 Chinese were killed within Batavia’s city walls, while at least another 500 were seriously wounded. Between 600 and 700 Chinese-owned houses were raided and burned. Figures say that between 600 and 3,000 Chinese survived. The massacre was followed by an “open season” against the ethnic Chinese throughout Java, causing another massacre in 1741 in Semarang, and others later in Surabaya and Gresik.

As part of conditions for the cessation of violence, all of Batavia’s ethnic Chinese were moved to a pecinan, or Chinatown, outside of the city walls, now known as Glodok. This allowed the Dutch to monitor the Chinese more easily. To leave the pecinan, ethnic Chinese required special passes.

Valckenier left the Indies on 6 November 1741 headed for the Netherlands. By this time, however, van Imhoff, had reported the massacre to the authorities in Netherlands, fully blaming Valckenier for the brutal events that happened in Batavia. On 25 January 1742, Valckenier arrived in Cape Town but was detained, and investigated by order of the Lords XVII.

In August 1742 Valckenier was sent back to Batavia, where he was imprisoned in Fort Batavia and, three months later, tried on several charges, including his involvement in the massacre. In March 1744 he was convicted and condemned to death, by this time, ethnic Chinese had already returned to inner Batavia; several hundred merchants operated there.

Dutch historian Leonard Blussé writes that the massacre indirectly led to the rapid expansion of Batavia, and institutionalised a modus vivendi that led to a dichotomy between the ethnic Chinese and other groups which could still be felt in the late 20th century.

The massacre may also have been a factor in the naming of numerous areas in Jakarta. One possible etymology for the name of the Tanah Abang district (meaning “red earth”) is that it was named for the Chinese blood spilled there. The name Rawa Bangke, for a subdistrict of East Jakarta, may be derived from the vulgar Indonesian word for corpse, bangkai, due to the great number of ethnic Chinese killed there; a similar etymology has been suggested for Angke in Tambora.

- Year c.1740

- Measurement: 330 x 250 mm

- Dimensions: 400 x 535 mm including frame

- Condition: Very good.

- Coloring: Black and White

- Technique: Copperplate engraving

- Purchase Code: P2751